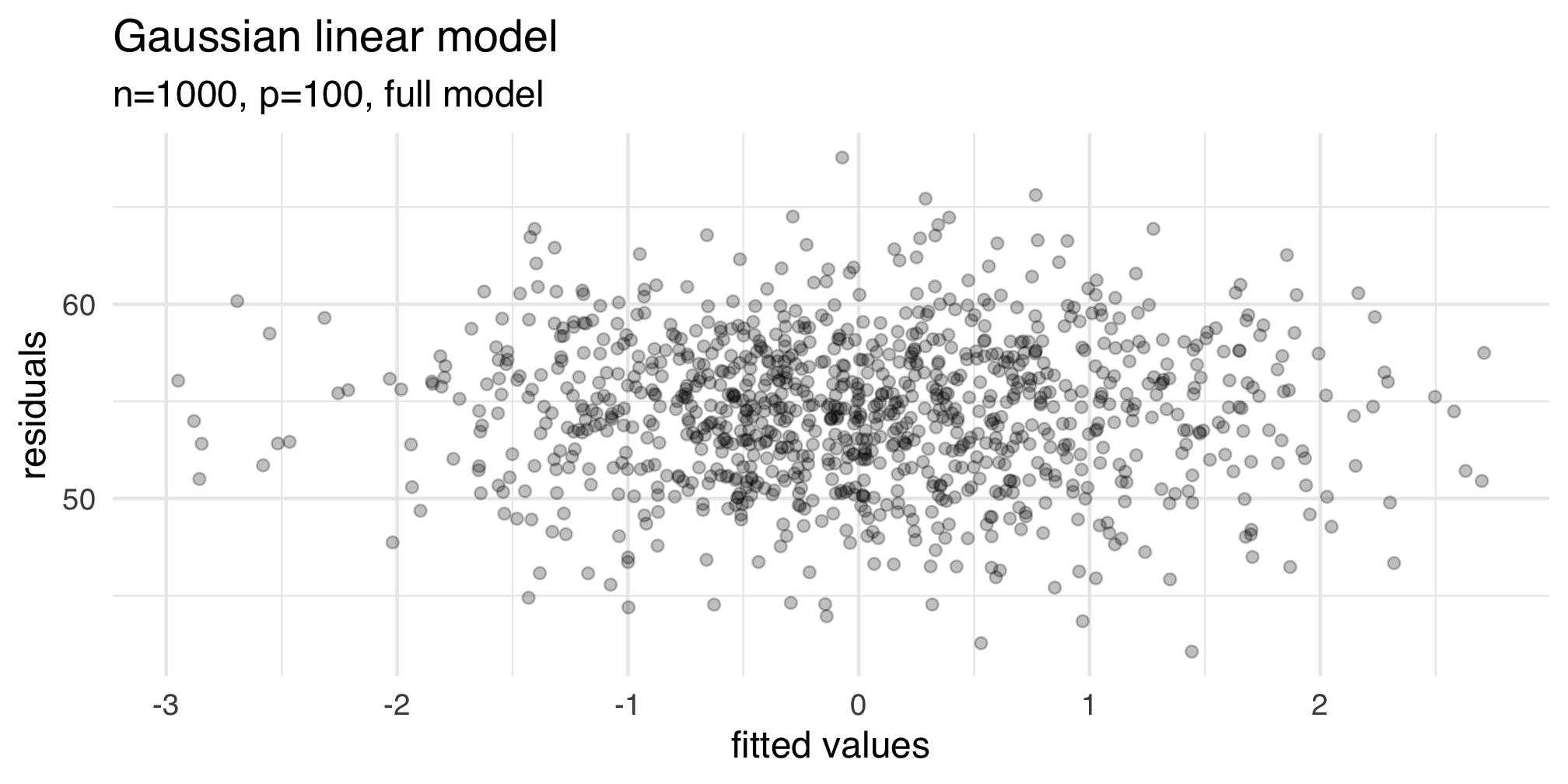

name: inter-slide class: left, middle, inverse {{ content }} --- name: layout-general layout: true class: left, middle <style> .remark-slide-number { position: inherit; } .remark-slide-number .progress-bar-container { position: absolute; bottom: 0; height: 4px; display: block; left: 0; right: 0; } .remark-slide-number .progress-bar { height: 100%; background-color: red; } </style> <div> <style type="text/css">.xaringan-extra-logo { width: 110px; height: 128px; z-index: 0; background-image: url(./img/Universite_Paris_logo_horizontal.jpg); background-size: contain; background-repeat: no-repeat; position: absolute; top:1em;right:1em; } </style> <script>(function () { let tries = 0 function addLogo () { if (typeof slideshow === 'undefined') { tries += 1 if (tries < 10) { setTimeout(addLogo, 100) } } else { document.querySelectorAll('.remark-slide-content:not(.hide_logo)') .forEach(function (slide) { const logo = document.createElement('a') logo.classList = 'xaringan-extra-logo' logo.href = 'http://master.math.univ-paris-diderot.fr/annee/m1-mi/' slide.appendChild(logo) }) } } document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', addLogo) })()</script> </div> --- template: inter-slide # Multilinear Regression II #### [Master I ISIFAR]() #### [Analyse de Données](http://stephane-v-boucheron.fr/courses/isidata/) #### [Stéphane Boucheron](http://stephane-v-boucheron.fr) --- class: inverse, middle ## <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 576 512" style="height:1em;width:1.12em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:white;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M0 117.66v346.32c0 11.32 11.43 19.06 21.94 14.86L160 416V32L20.12 87.95A32.006 32.006 0 0 0 0 117.66zM192 416l192 64V96L192 32v384zM554.06 33.16L416 96v384l139.88-55.95A31.996 31.996 0 0 0 576 394.34V48.02c0-11.32-11.43-19.06-21.94-14.86z"/></svg> ### Motivations ### Tidy approach to modeling ### Diagnostics ### Exploring models ### Algorithms ### Beyond Least Squares --- class: middle, center, inverse ## Motivations --- ### Questions - Assessing Linear modelling assumptions ??? --- class: middle, center, inverse ## Tidy approach to modeling ??? [Modern Dive](https://moderndive.com/index.html) --- class: middle, center, inverse ## Diagnostics ??? From Weisberg (Applied Regression, Chapter 8) > Regression diagnostics are used _after_ fitting to check if a fitted mean > function and assumptions are consistent with observed data. > The basic statistcs here are the residuals or possibly the rescaled residuals > If the fitted model does not give a set of residuals that appear to be reasonable, > then some aspect of the model, either the assumed mean function or assumptions > concerning the variance function may be called into doubt New concepts - distance measures - leverage values --- ### Residuals <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;width:1em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M201.5 174.8l55.7 55.8c3.1 3.1 3.1 8.2 0 11.3l-11.3 11.3c-3.1 3.1-8.2 3.1-11.3 0l-55.7-55.8-45.3 45.3 55.8 55.8c3.1 3.1 3.1 8.2 0 11.3l-11.3 11.3c-3.1 3.1-8.2 3.1-11.3 0L111 265.2l-26.4 26.4c-17.3 17.3-25.6 41.1-23 65.4l7.1 63.6L2.3 487c-3.1 3.1-3.1 8.2 0 11.3l11.3 11.3c3.1 3.1 8.2 3.1 11.3 0l66.3-66.3 63.6 7.1c23.9 2.6 47.9-5.4 65.4-23l181.9-181.9-135.7-135.7-64.9 65zm308.2-93.3L430.5 2.3c-3.1-3.1-8.2-3.1-11.3 0l-11.3 11.3c-3.1 3.1-3.1 8.2 0 11.3l28.3 28.3-45.3 45.3-56.6-56.6-17-17c-3.1-3.1-8.2-3.1-11.3 0l-33.9 33.9c-3.1 3.1-3.1 8.2 0 11.3l17 17L424.8 223l17 17c3.1 3.1 8.2 3.1 11.3 0l33.9-34c3.1-3.1 3.1-8.2 0-11.3l-73.5-73.5 45.3-45.3 28.3 28.3c3.1 3.1 8.2 3.1 11.3 0l11.3-11.3c3.1-3.2 3.1-8.2 0-11.4z"/></svg> `$$H = X \times (X^ T \times X)^{-1}\times X\qquad \text{Hat matrix}$$` `$$\widehat{\epsilon} = Y - \widehat{Y} = (\text{Id} -H) \epsilon \qquad\text{residuals}$$` Under Gaussian Linear Modeling Assumptions: - `\(\widehat{\epsilon} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2 (\text{Id} -H))\)` ??? The GLM Assumptions comprise different kind of assertions - noise has constant variance - noise is centered - noise is Gaussian - `\(\mathbb{E}Y\)` in a linear function of `\(\mathbf{X}\)` A corollary of those assumptions is that the distribution of residuals is symmetric --- ### Leverages The Hat matrix satisfies `$$\sum_{i=1}^n H_{i,i} = \text{rank}(X)$$` `$$0 \leq H_{i,i } \leq 1 \qquad \forall i \leq n$$` `$$\widehat{Y}_i = H_{i,i}Y_i + \sum_{j\neq i} H_{i, j} Y_j \qquad \forall i \leq n$$` `\(H_{i,i}\)` is called the leverage of the `\(i^{\text{th}}\)` case (row) ??? - Spectral properties of Projection matrices - If the design is orthogonal (with normed columns) `\(H = XX^T\)` - What does large or small leverages mean ? - What is a _typical_ leverage ? - The average leverage is `\(1/n\)` --- ### Leverages <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;width:1em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M512 199.652c0 23.625-20.65 43.826-44.8 43.826h-99.851c16.34 17.048 18.346 49.766-6.299 70.944 14.288 22.829 2.147 53.017-16.45 62.315C353.574 425.878 322.654 448 272 448c-2.746 0-13.276-.203-16-.195-61.971.168-76.894-31.065-123.731-38.315C120.596 407.683 112 397.599 112 385.786V214.261l.002-.001c.011-18.366 10.607-35.889 28.464-43.845 28.886-12.994 95.413-49.038 107.534-77.323 7.797-18.194 21.384-29.084 40-29.092 34.222-.014 57.752 35.098 44.119 66.908-3.583 8.359-8.312 16.67-14.153 24.918H467.2c23.45 0 44.8 20.543 44.8 43.826zM96 200v192c0 13.255-10.745 24-24 24H24c-13.255 0-24-10.745-24-24V200c0-13.255 10.745-24 24-24h48c13.255 0 24 10.745 24 24zM68 368c0-11.046-8.954-20-20-20s-20 8.954-20 20 8.954 20 20 20 20-8.954 20-20z"/></svg> Assume that the columns of `\(\mathbf{X}\)` are centered (have zero mean) Denote by `\(X_i\)` the `\(i^{th}\)` column of `\(\mathbf{X}^T\)` `$$H_{i,i} = X_i^T \times (\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X})^{-1} \times X_i$$` Lines `\(r^2 = x^T \times (\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X})^{-1} \times x\)` are centered ellipses with axes defined by the eigen vectors of `\(\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X}\)` ??? Assuming that the columns of `\(\mathbf{X}\)` are centered means that `\(1\)` is in the kernel (nullspace) of the Hat matrix --- ### Inspection of leverages for designs connected to `cystfibr` .panelset[ .panel[.panel-name[`pemax ~ age`] ] .panel[.panel-name[`pemax ~ .`] ] .panel[.panel-name[Comments] ] ] ??? > In some problems, high-leverage points with values close to `\(1\)` can occur, and > identifying these cases is very useful in understanding a regression problem Weisberg p. 170 --- ### Standardized residuals --- class: middle, center, inverse ## Leave One Out (LOO)/Jackknife --- ### Notation .fl.w-50.pa2[ - `\(Y^{(i)}\)`: `\(Y\)` deprived from `\(i^{\text{th}}\)` coordinate - `\(\mathbf{X}^{(i)}\)`: designed deprived from `\(i^{\text{th}}\)` row - `\(\epsilon^{(i)}\)`: `\(ϵ\)` deprived from `\(i^{\text{th}}\)` coordinate ] -- .fl.w-50.pa2[ - `\(\widehat{\theta}^{(i)}\)`: minimizer of `\(\big\|Y^{(i)} -\mathbf{X}^{(i)}ϑ \big\|^2_2\)` `$$\widehat{\theta}^{(i)} = \left({\mathbf{X}^{(i)}}^T\mathbf{X}^{(i)}\right)^{-1}{\mathbf{X}^{(i)}}^T$$` - `\(\widehat{Y}^{(i)} = \mathbf{X} \widehat{\theta}^{(i)}\)` ] ??? These objects obtained by removing the `\(i^{\text{th}}\)` observation from the data. Comparing `\(\widehat{\theta}\)` and `\(\widehat{\theta}^{(i)}\)` tells us about the _influence_ of the `\(i^{\text{th}}\)` sample point --- ### A weighted `\(\ell_2\)` distance from `\(\widehat{\theta}\)` `$$D(ϑ, \widehat{\theta})= \frac{1}{p \widehat{\sigma}^2} (ϑ -\widehat{\theta})^T × \big(\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X}\big)× (ϑ -\widehat{\theta})$$` --- ### Cook's distance .bg-light-gray.b--dark-gray.ba.bw1.br3.shadow-5.ph4.mt5[ `$$D_i = D(\widehat{\theta}^{(i)}, \widehat{\theta})= \frac{1}{p \widehat{\sigma}^2} (\widehat{\theta}^{(i)} -\widehat{\theta})^T × \big(\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X}\big) × (\widehat{\theta}^{(i)} -\widehat{\theta})$$` ] This is a weighted `\(\ell_2\)` distance between `\(\widehat{\theta}\)` and `\(\widehat{\theta}^{(i)}\)`, the OLS solution obtained by removing the `\(i^{\text{th}}\)` observation. ??? Cook (1977) Cook's distance is a statistic --- ### Using `\(D_i\)` Deleting observations with large values of `\(D_i\)` results in substantial changes in the analysis Observations with the largest few `\(D_i\)` are o special interest ??? --- If `\(D_i\)` were exactly equal to the `\(\alpha\)` quantile of `\(F_{p, n-p}\)` distribution, then deleting the `\(i^{\text{th}}\)` observation would move the estimate of `\(\widehat{\beta}\)` to the edge of `\(1-\alpha\)` confidence region based on the complete dataset --- ### Efficient computation of Cook's distances `$$D_i = \frac{1}{p} \frac{H_{i,i}}{(1 - H_{i,i})^2} \frac{\left(Y_i - \widehat{Y}_i\right)^2}{\widehat{\sigma}^2}$$` -- If all leverages are `\(1/n\)` `$$\sum_{i=1}^n D_i =$$` --- ### LOOCV ??? - Ouverture to resampling method - Jackknife - Bootstrap - Cross-Validation --- ### - `\(\widehat{Y}^{(i)}_i = X_i^T \widehat{\theta}^{(i)}\)` is a linear function of `\(ϵ^{(i)}\)` - `\(Y_i\)` is a linear function of `\(\epsilon_i\)` -- - `\(Y_i\)` and `\(\widehat{Y}^{(i)}_i\)` are stochastically independent - We do not need to assume that the noise is Gaussian to ensure that --- - If noise is centered `$$\mathbb{E}\left[Y_i - \widehat{Y}^{(i)}_i\right] = 0$$` `$$\mathbb{E}\left[\left(Y_i - \widehat{Y}^{(i)}_i\right)^2\right] = \sigma^2 (1+ H_{i,i})$$` - If noise is Gaussian `$$Y_i - \widehat{Y}^{(i)}_i \sim \mathcal{N}\left(0, \sigma^2 \left(1+ X_i^T \left({\mathbf{X}^{(i)}}^T \mathbf{X}^{(i)}\right)^{-1}X_i\right)\right)$$` with `$$X_i^T \left({\mathbf{X}^{(i)}}^T \mathbf{X}^{(i)}\right)^{-1}X_i = H_{i,i}$$` --- `$$\mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{i=1}^n \left(Y_i - \widehat{Y}^{(i)}_i\right)^2\right] = \sigma^2 (n+p)$$` ??? Computing the LOOCV estimate `$$\sum_{i=1}^n \left(Y_i - \widehat{Y}^{(i)}_i\right)^2$$` looks demanding --- ### Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation formula `$$\sum_{i=1}^n \left(Y_i - \widehat{Y}^{(i)}_i\right)^2 = \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{(Y_i - \widehat{Y}_i)^2}{(1-H_{i,i})^2}$$` ??? One of the most beautiful formulae in statistics --- ### Shermann-Morrison formula (redux) Let `\(\mathbf{A}\)` be an invertible square matrix and `\(u, v\)` be two vectors - `\(\mathbf{A}+ u\,v^T\)` is invertible iff `\(1 + v^T \mathbf{A}^{-1} u \neq 0\)` - if `\(1 + v^T \mathbf{A}^{-1} u \neq 0\)` `$$\left(\mathbf{A} + u\,v^T\right)^{-1} = \mathbf{A}^{-1} - \frac{1}{1 + v^T \mathbf{A}^{-1} u} \mathbf{A}^{-1} uv^T \mathbf{A}^{-1}$$` ?? The inverse of a rank-one perturbation is a rank-one perturbation of the inverse --- ### Proof of Shermann-Morrison formula If `\(\mathbf{A} + u\,v^T\)` is not invertible, there exists a non-zero vector `\(w\)` such that `$$\mathbf{A} w + u\, v^T\, w=0$$` Note that this implies `\(v^T\, w\neq 0\)` This also implies `\(v^T w + v^T \mathbf{A}^{-1} u v^T w=0\)` And thus `\(1 + v^T \mathbf{A}^{-1} u = 0\)` --- ### Proof of Shermann-Morrison formula (continued) Conversely, if `\(1 + v^T \mathbf{A}^{-1} u = 0\)` `$$\left(\mathbf{A} + u v^T\right)× \left(\mathbf{A}^{-1} u\right) = u \left(1 + v^T \mathbf{A}^{-1} u\right)=0$$` This implies that `\(\mathbf{A} + u v^T\)` is not invertible --- ### Proof of Shermann-Morrison formula (continued) To check the formula, first check the easier formula `$$\left(\mathbf{Id} + xy^T \right)^{-1} = \mathbf{Id} - \frac{1}{1+ y^Tx} xy^T$$` for `\(1 + y^Tx\neq 0\)` Then use this formula with `\(x=\mathbf{A}^{-1}u\)` and `\(y=v\)` <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 448 512" style="height:1em;width:0.88em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M400 32H48C21.5 32 0 53.5 0 80v352c0 26.5 21.5 48 48 48h352c26.5 0 48-21.5 48-48V80c0-26.5-21.5-48-48-48z"/></svg> --- ### Proof of LOOCV formula Let `\(\mathbf{X}\)` denote the design matrix Let `\(X_i\)` denote the `\(i^{\text{th}}\)` column of `\(\mathbf{X}^T\)` Let `\(\mathbf{X}^{(i)}\)` denote the design matrix deprived from its `\(i^{\text{th}}\)` row `$$\mathbf{X}^T \times \mathbf{X} = \left({\mathbf{X}^{(i)}}^T \mathbf{X}^{(i)}\right) + X_i X_i^T$$` <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;width:1em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M512 199.652c0 23.625-20.65 43.826-44.8 43.826h-99.851c16.34 17.048 18.346 49.766-6.299 70.944 14.288 22.829 2.147 53.017-16.45 62.315C353.574 425.878 322.654 448 272 448c-2.746 0-13.276-.203-16-.195-61.971.168-76.894-31.065-123.731-38.315C120.596 407.683 112 397.599 112 385.786V214.261l.002-.001c.011-18.366 10.607-35.889 28.464-43.845 28.886-12.994 95.413-49.038 107.534-77.323 7.797-18.194 21.384-29.084 40-29.092 34.222-.014 57.752 35.098 44.119 66.908-3.583 8.359-8.312 16.67-14.153 24.918H467.2c23.45 0 44.8 20.543 44.8 43.826zM96 200v192c0 13.255-10.745 24-24 24H24c-13.255 0-24-10.745-24-24V200c0-13.255 10.745-24 24-24h48c13.255 0 24 10.745 24 24zM68 368c0-11.046-8.954-20-20-20s-20 8.954-20 20 8.954 20 20 20 20-8.954 20-20z"/></svg> `\({\mathbf{X}^{(i)}}^T \mathbf{X}^{(i)}\)` is a rank one perturbation of `\(\mathbf{X}^T \times \mathbf{X}\)` --- ### Proof of LOOCV formula (continued) $$$$ <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 448 512" style="height:1em;width:0.88em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M400 32H48C21.5 32 0 53.5 0 80v352c0 26.5 21.5 48 48 48h352c26.5 0 48-21.5 48-48V80c0-26.5-21.5-48-48-48z"/></svg> --- ### Proof --- class: middle, center, inverse ## Exploring models: Variable selection in Gaussian Linear Models --- ### Exploring the `cysticfibr` data .panelset[ .panel[.panel-name[Data] ```r pacman::p_load('ISwR') cystfibr <- ISwR::cystfibr cystfibr <- cystfibr %>% mutate(sex=forcats::fct_recode(factor(sex), Male="0", Female="1")) p <- cystfibr %>% ggplot() + aes(y=pemax) + geom_point() + geom_smooth(method="lm", se=FALSE, formula = 'y ~ x') ``` ] ,panel[.panel-name[No effect versus some effect] ] .panel[.panel-name[$p$-value paradox] - Fisher test suggests some effect - None of the Student's tests is suggestive - Fisher test suggests some effect due to variables that are not related to lung function ] ] --- exclude: true --- ### Simple linear regression contest around `cysticfibr` .panelset[ .panel[.panel-name[Height] .fl.w-50.pa2[ <img src="cm-5-EDA_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-4-1.png" width="504" /> ] .fl.w-50.pa2[ - Simple linear regression ``` lm(pemax ~ height, cystfibr) ``` - The fact that Adjusted R-Squared is not close to `\(1\)` tells us that `height` does not predict `pemax` very accurately - A poor value of Adjusted R-Squared does not mean that the Gaussian Linear Modeling assumption is not valid ] ] .panel[.panel-name[Sex] .fl.w-50.pa2[ <img src="cm-5-EDA_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-5-1.png" width="504" /> ] .fl.w-50.pa2[ ``` lm(pemax ~ sex, cystfibr) ``` - `sex` is a factor (grey points are obtained by jittering) - `sex` is a poor predictor of `pemax` ] ] .panel[.panel-name[Age] .fl.w-50.pa2[ <img src="cm-5-EDA_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-6-1.png" width="504" /> ] .fl.w-50.pa2[ ``` lm(pemax ~ age, cystfibr) ``` - Looks very much like `lm(pemax ~ height, cystfibr)` ] ] .panel[.panel-name[About age and height] .fl.w-50.pa2[ <img src="cm-5-EDA_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-7-1.png" width="504" /> ] .fl.w-50.pa2[ ``` lm(height ~ age, cystfibr) ``` - `age` predicts `height` much better than it predicts `pemax` - does larger `R squared` mean model is more relevant? - what does this large `R squared` tell us about the respective merits of `age` and `height` when trying to predict `pemax`? ] ] .panel[.panel-name[Discussion] We can play that game with all covariates We end up with competing fits It is hard to tell which fits are the best Diagnostic statistics help us in deciding whether using a covariate is better than using no covariate at all Diagnostic statistics complement graphical inspection <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;width:1em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M504 256c0 136.997-111.043 248-248 248S8 392.997 8 256C8 119.083 119.043 8 256 8s248 111.083 248 248zM262.655 90c-54.497 0-89.255 22.957-116.549 63.758-3.536 5.286-2.353 12.415 2.715 16.258l34.699 26.31c5.205 3.947 12.621 3.008 16.665-2.122 17.864-22.658 30.113-35.797 57.303-35.797 20.429 0 45.698 13.148 45.698 32.958 0 14.976-12.363 22.667-32.534 33.976C247.128 238.528 216 254.941 216 296v4c0 6.627 5.373 12 12 12h56c6.627 0 12-5.373 12-12v-1.333c0-28.462 83.186-29.647 83.186-106.667 0-58.002-60.165-102-116.531-102zM256 338c-25.365 0-46 20.635-46 46 0 25.364 20.635 46 46 46s46-20.636 46-46c0-25.365-20.635-46-46-46z"/></svg> We wonder whether adding more covariates would help ] ] --- ### Simulated data ```r set.seed(1515) n <- 1000 p <- 10 B <- 2000 s <- 5 sigma <- 1 ``` --- ### Regular grid, polynomials Use function `poly()` to create a design matrix with `n` rows and `p` columns. The `\(i^{\text{th}}\)` row is made of `\((x_i^k)_{k=0, \ldots, p-1}\)` with `\(x_i= \frac{i}{n+1}\)`. Call the design `\(Z\)`, name the columns `x0, x1, ...`. ```r grid <- (1:n)/(n+1) Z <- cbind(rep(1,n), poly(grid, degree=p-1, raw = TRUE)) Z <- as.data.frame(Z) colnames(Z) <- stringr::str_c("x", 0:(p-1), sep = "") glimpse(Z) ``` ``` ## Rows: 1,000 ## Columns: 10 ## $ x0 <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1… ## $ x1 <dbl> 0.000999001, 0.001998002, 0.002997003, 0.003996004, 0.004995005, 0.… ## $ x2 <dbl> 9.980030e-07, 3.992012e-06, 8.982027e-06, 1.596805e-05, 2.495007e-0… ## $ x3 <dbl> 9.970060e-10, 7.976048e-09, 2.691916e-08, 6.380838e-08, 1.246257e-0… ## $ x4 <dbl> 9.960100e-13, 1.593616e-11, 8.067681e-11, 2.549786e-10, 6.225062e-1… ## $ x5 <dbl> 9.950150e-16, 3.184048e-14, 2.417886e-13, 1.018895e-12, 3.109422e-1… ## $ x6 <dbl> 9.940209e-19, 6.361734e-17, 7.246413e-16, 4.071510e-15, 1.553158e-1… ## $ x7 <dbl> 9.930279e-22, 1.271076e-19, 2.171752e-18, 1.626977e-17, 7.758031e-1… ## $ x8 <dbl> 9.920359e-25, 2.539612e-22, 6.508747e-21, 6.501406e-20, 3.875140e-1… ## $ x9 <dbl> 9.910448e-28, 5.074150e-25, 1.950674e-23, 2.597965e-22, 1.935634e-2… ``` --- ### QR factorization .bg-light-gray.b--dark-gray.ba.bw1.br3.shadow-5.ph4.mt5[ Let `\(Z\)` be an `\(n \times p\)` matrix with rank `\(r\)` There exist two matrices `\(Q\)` and `\(R\)` such that `$$Z = Q \times R$$` and - `\(Q\)` is an `\(n \times r\)` matrix with `\(Q^T \times Q = \text{Id}_r\)` (the columns of `\(Q\)` are standardized and pairwise orthogonal) - `\(R\)` is upper-triangular `\(r \times p\)` matrix with non-negative diagonal coefficient ] ??? - Applying the Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization procedure to matrix `\(Z\)` eventually leads to QR factorization - The QR factorization should not be computed using Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization! - The columns of `\(Q\)` form an orthonormal basis of the linear space spanned by the columns of `\(Z\)` --- ### Design properties The performance of Multiple Linear Regression depends on the conditionning of `\(Z\)`, namely on the operator norm of `\((Z^T Z)^{-1}\)` - Compute the QR decomposition of the design matrix - Compute the _pseudo-inverse_ of the design matrix --- ```r qrz <- qr(as.matrix(Z)) foo <- qr.Q(qrz) bar <- qr.R(qrz) H <- t(foo) %*% foo ``` --- ### Linear models with fixed design Generate a random polynomial of degree `p-1` with `s` non-null coefficients `\(1, 2, \ldots, s\)`. The position of the non-null coefficients is random. ```r ix <- sort(sample(1:p, s)) betas <- rep(0, p) betas[ix] <- 1:s ``` --- Generate an instance of the linear model: `$$\begin{bmatrix} y_1 \\ \vdots\\ y_n\end{bmatrix} = \underbrace{\begin{bmatrix} 1 & x^1_1 & \ldots & x_1^{p-1} \\ \vdots & & & \vdots \\ 1 & x^1_n & \ldots & x_n^{p-1} \\ \end{bmatrix}}_{Z} \times \begin{bmatrix} \beta_0\\ \vdots \\ \beta^{p-1}\end{bmatrix} + \sigma \begin{bmatrix} \epsilon_1 \\ \vdots \\ \epsilon_n \end{bmatrix}$$` --- ```r # TODO: # df <- .... # assertthat::assert_that(all(names(df) == c("x0", "x1", "x2", "x3", "x4", "x5", "x6", "x7", "x8", "x9", "Y"))) ``` --- Compute the least squares estimate of `\(\beta\)` given `\(Z\)` and `\(Y\)`. Use `qr.solve()` and `lm()`. Compare the results. ```r # TODO: ``` Comment the output of `summary(.)` ```r # TODO ``` --- - Provide an interpretation of each `\(t\)` value - Provide an interpretation of `Pr(>|t|)` - Explain why the `Residual standard error` has `990` degrees of freedom. - How is `Residual standard error` computed? - What is `Residual standard error` supposed to estimate? - Is it an unbiased estimator? - What is `Multiple R-squared` ? - What is `Adjusted R-squared` ? - How do you reconcile the values of `Pr(>|t|)` and the `p-value` of the `F-statistic` --- Have a look at the body of `summary` method for class `lm` (`summary.lm`). ```r # TODO: ``` Plot `\(Y\)` and fitted values `\(\widehat{Y}\)` against `\(x\)` (second column of design, `x^1`). ```r # TODO: ``` --- ### Analysis of variance Fit the minimal model (polynomial of degree `\(0\)`) to your observations ```r # TODO: lm00 <- ... ``` Compare minimal model and full model with function `anova` ```r # TODO: anova(., .) ``` --- ### Variable selection Package `MASS` offers function `stepAIC` to perform variable selection ```r require(MASS) ``` We pick another model with the same design matrix, but the estimand `\(\beta\)` shall be 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 ```r betas <- c(5:1, rep(0, 5)) # df2 <- .. ``` --- Fit polynomials of degree `0` up to `9` to the new data You may define the formulas in different ways. This is pedestrian. You may also use `poly()`. ```r formulas <- purrr::map_chr(0:9 , .f = ~ stringr::str_c("x", 0:., collapse = " + ")) %>% stringr::str_c("Y ~ ", .) %>% stringr::str_c( " - 1") %>% purrr::map(formula) ``` --- Plot sums of squared residuals as a function of order. ```r # TODO: ``` Perform `anova` analysis between polynomial model of degree `i` and polynomial model of degree `i + 1` for `0 <= i <9`. ```r # TODO: anova(., .) ``` --- ### ... ```r # TODO: ``` Use function `aov()`, comment result and summary. ```r # TODO: # df2.aov <- aov(formula = ., data = df2) # df2.aov ``` --- ### ... Update `df2.aov` using function `update`. Drop `x5, x6, x7, x8, x9` ```r # TODO: update(df2.aov, . ~ . - x5 - x6 - x7 - x8 - x9) ``` Use function `dropterm` on full model with option `test = "F"` and without. Interpret in both cases. ```r # TODO: dropterm(df2.aov, ...) ``` --- ### Using `addterm` between minimal and full model ```r # TODO: ``` --- class: center, middle, inverse ## Choose a model by AIC in a Stepwise Algorithm --- ### AIC : Akaike Information Criterion --- --- ### Using `stepAIC()` - `stats::step()` - - `MASS::stepAIC()` --- - Choose a model by AIC in a Stepwise Algorithm Use function `stepAIC()` to search for a good balance between model complexity and goodness of fit ```r # TODO ``` --- ### ANOVA In the sequel of this section, we use simulated data to introduce and motivate the ANOVA method. We generate - a design matrix `\(Z \in \mathcal{M}_{n,p}\)` with `\(n=1000\)` and `\(p=100\)`, - a sparse random vector `\(\theta \in \mathbb{R}^p\)` - a vector of observation `\(Y = Z \times \theta + \sigma \epsilon\)` where `\(\sigma=1\)` and `\(\epsilon\)` is a standard Gaussian vector of dimension `\(p\)`. --- count: false ### Preparing ANOVA ```r *set.seed(1515) # for reproducibility ``` --- count: false ### Preparing ANOVA ```r set.seed(1515) # for reproducibility *p <- 100 # dimension of sample points ``` --- count: false ### Preparing ANOVA ```r set.seed(1515) # for reproducibility p <- 100 # dimension of sample points *n <- 1000 # sample size ``` --- count: false ### Preparing ANOVA ```r set.seed(1515) # for reproducibility p <- 100 # dimension of sample points n <- 1000 # sample size *sigma <- 1 # noise standard deviation ``` --- count: false ### Preparing ANOVA ```r set.seed(1515) # for reproducibility p <- 100 # dimension of sample points n <- 1000 # sample size sigma <- 1 # noise standard deviation *betas <- matrix(rbinom(p, 1, 0.1) * rnorm(p, mean=1), * nrow=p, ncol=1) # true coefficient vector ``` --- count: false ### Preparing ANOVA ```r set.seed(1515) # for reproducibility p <- 100 # dimension of sample points n <- 1000 # sample size sigma <- 1 # noise standard deviation betas <- matrix(rbinom(p, 1, 0.1) * rnorm(p, mean=1), nrow=p, ncol=1) # true coefficient vector *important_coeffs <- which(abs(betas) >.01) # sparse support ``` --- count: false ### Preparing ANOVA ```r set.seed(1515) # for reproducibility p <- 100 # dimension of sample points n <- 1000 # sample size sigma <- 1 # noise standard deviation betas <- matrix(rbinom(p, 1, 0.1) * rnorm(p, mean=1), nrow=p, ncol=1) # true coefficient vector important_coeffs <- which(abs(betas) >.01) # sparse support *Z <- matrix(rnorm(n*p, 5), ncol = p, nrow=n) # design ``` --- count: false ### Preparing ANOVA ```r set.seed(1515) # for reproducibility p <- 100 # dimension of sample points n <- 1000 # sample size sigma <- 1 # noise standard deviation betas <- matrix(rbinom(p, 1, 0.1) * rnorm(p, mean=1), nrow=p, ncol=1) # true coefficient vector important_coeffs <- which(abs(betas) >.01) # sparse support Z <- matrix(rnorm(n*p, 5), ncol = p, nrow=n) # design *Y <- Z %*% betas + matrix(rnorm(n, 0, sd=sigma), nrow=n) ``` --- count: false ### Preparing ANOVA ```r set.seed(1515) # for reproducibility p <- 100 # dimension of sample points n <- 1000 # sample size sigma <- 1 # noise standard deviation betas <- matrix(rbinom(p, 1, 0.1) * rnorm(p, mean=1), nrow=p, ncol=1) # true coefficient vector important_coeffs <- which(abs(betas) >.01) # sparse support Z <- matrix(rnorm(n*p, 5), ncol = p, nrow=n) # design Y <- Z %*% betas + matrix(rnorm(n, 0, sd=sigma), nrow=n) *df <- as.data.frame(cbind(Z, Y), ) ``` --- count: false ### Preparing ANOVA ```r set.seed(1515) # for reproducibility p <- 100 # dimension of sample points n <- 1000 # sample size sigma <- 1 # noise standard deviation betas <- matrix(rbinom(p, 1, 0.1) * rnorm(p, mean=1), nrow=p, ncol=1) # true coefficient vector important_coeffs <- which(abs(betas) >.01) # sparse support Z <- matrix(rnorm(n*p, 5), ncol = p, nrow=n) # design Y <- Z %*% betas + matrix(rnorm(n, 0, sd=sigma), nrow=n) df <- as.data.frame(cbind(Z, Y), ) *names(df) <- c(paste("x", 1:p, sep="_"), "y") ``` <style> .panel1-my_simul_anova-auto { color: black; width: 99%; hight: 32%; float: left; padding-left: 1%; font-size: 80% } .panel2-my_simul_anova-auto { color: black; width: NA%; hight: 32%; float: left; padding-left: 1%; font-size: 80% } .panel3-my_simul_anova-auto { color: black; width: NA%; hight: 33%; float: left; padding-left: 1%; font-size: 80% } </style> --- ### True model versus full model Dataframe `df` fits Gaussian linear modeling assumptions We may feed it to `lm()` This leads to what we call the _full model_ We may also take advantage of the fact that we know which columns of `\(Z\)` matters when we want to predict `\(Y\)`. Hence, we can compare the linear model obtained by brute force `lm(y ~ . -1, df)` ( `\(-1\)` because we need no intercept) with the linear model obtained by using columns of `df` corresponding to non-null coefficients of `betas` We call the former the _true model_ --- ### Building formulae ```r formula_full <- formula("y ~ . - 1") formula_true <- formula(str_c("y", paste(str_c("x", important_coeffs, sep = "_"), collapse =" + "), sep=" ~ ")) formulae <- c(formula_full, formula_true) lm_df <- map(formulae, lm, data=df) names(lm_df) <- c("full", "true") ``` --- ### The true model ```r formula_true ``` ``` ## y ~ x_2 + x_9 + x_22 + x_27 + x_41 + x_49 + x_52 + x_53 + x_59 + ## x_60 + x_77 + x_88 + x_93 ``` --- ### Comparing reconstruction errors We can compare the true and full models using the quadratic error criterion. The residuals can be gathered from both models using function `residuals()`. The Residual Sum of Squares (RSS) are respectively 885.4 for the full model and 957.5. At first glance, the full model achieves a better fit to the data than the true model --- ### Comparing estimation errors <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 576 512" style="height:1em;width:1.12em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M569.517 440.013C587.975 472.007 564.806 512 527.94 512H48.054c-36.937 0-59.999-40.055-41.577-71.987L246.423 23.985c18.467-32.009 64.72-31.951 83.154 0l239.94 416.028zM288 354c-25.405 0-46 20.595-46 46s20.595 46 46 46 46-20.595 46-46-20.595-46-46-46zm-43.673-165.346l7.418 136c.347 6.364 5.609 11.346 11.982 11.346h48.546c6.373 0 11.635-4.982 11.982-11.346l7.418-136c.375-6.874-5.098-12.654-11.982-12.654h-63.383c-6.884 0-12.356 5.78-11.981 12.654z"/></svg> This comparison is not fair The full model is obtained by optimizing the quadratic error over a set which is much larger than the set used for the true model As we are handling simulated data, we can compare the coefficient estimates in the two models and see whether one comes closer to the coefficients used to generate the data The squared `\(\ell_2\)` distances to `\(\theta\)` are substantially different: `$$\| \theta - \widehat{\theta}^{\text{true}}\|^2 = 1.31 \times 10^{-2}$$` while `$$\| \theta - \widehat{\theta}^{\text{full}}\|^2 = 9.75 \times 10^{-2}$$` --- ### Overfitting The fact that the full model outperforms the small model with respect to the Residual Sum of Squares criterion is righteously called _overfitting_. --- ### Diagnosing the full model .panelset[ .panel[.panel-name[Code] ```r xx <- residuals(lm_df[['full']]) yy <- fitted.values(lm_df[['full']]) qplot(y=yy, x=xx, alpha=I(.25)) + xlab("fitted values") + ylab("residuals") + ggtitle("Gaussian linear model", subtitle = "n=1000, p=100, full model") ``` ] .panel[.panel-name[Residuals versus Fitted plot]  ] ] --- ### ```r head((anova(lm_df[['full']])) %>% broom::tidy(.n), 10) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 10 × 6 ## term df sumsq meansq statistic p.value ## <chr> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 x_1 1 2852285. 2852285. 2899391. 0 ## 2 x_2 1 85346. 85346. 86755. 0 ## 3 x_3 1 10823. 10823. 11002. 0 ## 4 x_4 1 5974. 5974. 6072. 0 ## 5 x_5 1 3901. 3901. 3965. 0 ## 6 x_6 1 2053. 2053. 2086. 1.23e-236 ## 7 x_7 1 1990. 1990. 2023. 1.96e-232 ## 8 x_8 1 1153. 1153. 1172. 4.21e-165 ## 9 x_9 1 4715. 4715. 4793. 0 ## 10 x_10 1 1032. 1032. 1049. 3.69e-153 ``` --- count: false ### Residual distribution (full model) .panel1-kde_residuals-auto[ ```r *tib ``` ] .panel2-kde_residuals-auto[ ``` ## # A tibble: 1,000 × 1 ## residuals ## <dbl> ## 1 -0.319 ## 2 0.427 ## 3 -0.495 ## 4 0.0399 ## 5 0.302 ## 6 -0.920 ## 7 -0.0672 ## 8 -1.64 ## 9 -0.475 ## 10 -0.954 ## # … with 990 more rows ``` ] --- count: false ### Residual distribution (full model) .panel1-kde_residuals-auto[ ```r tib %>% * ggplot(aes(x=residuals)) ``` ] .panel2-kde_residuals-auto[ <img src="cm-5-EDA_files/figure-html/kde_residuals_auto_02_output-1.png" width="504" /> ] --- count: false ### Residual distribution (full model) .panel1-kde_residuals-auto[ ```r tib %>% ggplot(aes(x=residuals)) + * geom_histogram(aes(y=..density..), * alpha=.3) ``` ] .panel2-kde_residuals-auto[ ``` ## `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`. ``` <img src="cm-5-EDA_files/figure-html/kde_residuals_auto_03_output-1.png" width="504" /> ] --- count: false ### Residual distribution (full model) .panel1-kde_residuals-auto[ ```r tib %>% ggplot(aes(x=residuals)) + geom_histogram(aes(y=..density..), alpha=.3) + * stat_density(kernel = "epanechnikov", * bw = .15, * alpha=.0, * col=1) ``` ] .panel2-kde_residuals-auto[ ``` ## `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`. ``` <img src="cm-5-EDA_files/figure-html/kde_residuals_auto_04_output-1.png" width="504" /> ] --- count: false ### Residual distribution (full model) .panel1-kde_residuals-auto[ ```r tib %>% ggplot(aes(x=residuals)) + geom_histogram(aes(y=..density..), alpha=.3) + stat_density(kernel = "epanechnikov", bw = .15, alpha=.0, col=1) + * stat_function(fun = dnorm, * args=list(mean=m, * sd=s), * linetype=2) ``` ] .panel2-kde_residuals-auto[ ``` ## `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`. ``` <img src="cm-5-EDA_files/figure-html/kde_residuals_auto_05_output-1.png" width="504" /> ] --- count: false ### Residual distribution (full model) .panel1-kde_residuals-auto[ ```r tib %>% ggplot(aes(x=residuals)) + geom_histogram(aes(y=..density..), alpha=.3) + stat_density(kernel = "epanechnikov", bw = .15, alpha=.0, col=1) + stat_function(fun = dnorm, args=list(mean=m, sd=s), linetype=2) + * ggtitle(tit, * "Dashed curve: Gaussian fit") ``` ] .panel2-kde_residuals-auto[ ``` ## `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`. ``` <img src="cm-5-EDA_files/figure-html/kde_residuals_auto_06_output-1.png" width="504" /> ] <style> .panel1-kde_residuals-auto { color: black; width: 38.6060606060606%; hight: 32%; float: left; padding-left: 1%; font-size: 80% } .panel2-kde_residuals-auto { color: black; width: 59.3939393939394%; hight: 32%; float: left; padding-left: 1%; font-size: 80% } .panel3-kde_residuals-auto { color: black; width: NA%; hight: 33%; float: left; padding-left: 1%; font-size: 80% } </style> --- ### Assessing residuals ```r shapiro.test(residuals(lm_df[['full']])) ``` ``` ## ## Shapiro-Wilk normality test ## ## data: residuals(lm_df[["full"]]) ## W = 0.99752, p-value = 0.134 ``` ```r # (coefficients(lm.1)[1])^2 + norm(betas - coefficients(lm.1)[-1])^2 # norm(betas - lm.0$coefficients)^2 ``` --- class: middle, center, inverse ## Using Fisher `\(F\)` statistic --- ### Computing the Fisher `\(F\)` statistic for comparing model 0 and model 1 As we are dealing with simulated data, we can behave as if a benevolent _oracle_ had whispered that all but `97` coefficients are null, and even told us the index of the non-null coefficients. We fit this exact and minimal model to the data. Under the Gaussian linear model assumption, the empirical distribution of residuals is the empirical distribution of the projection of a standard Gaussian vector onto the linear subspace orthogonal to the subspace generated by the design columns. As such the distribution of residuals is not the empirical distribution of an i.i.d Gaussian sample. Nevertheless, if the linear subspace is not too correlated with the canonical basis, the residuals empirical distribution is not too far from a Gaussian distribution. --- exclude: true <div class="figure"> <img src="cm-5-EDA_files/figure-html/residdistrib-1.png" alt="(ref:residdistrib)" width="504" /> <p class="caption">(ref:residdistrib)</p> </div> --- ### Comparing true model and full model We are facing a _binary hypotheses problem_. - Null hypothesis: all coefficients but `x_2 , x_9 , x_22 , x_27 , x_41 , x_49 , x_52 , x_53 , x_59, x_60 , x_77 , x_88 , x_93` are null - Alternative hypothesis: the vector of coefficients doesnot satisfy the `\(13\)` linear equations defining the null hypothesis Note that both the null and alternative hypotheses are composite. --- The null hypothesis asserts that the true vector of coefficients belong to a linear subspace of dimension `13` of `\(\mathbb{R}^{100}\)`. If we stick to Gaussian linear modelling we may test this null hypothesis by performing a _Fisher test_. Under the null hypothesis, `$$\frac{\|\widehat{Y} - \widehat{Y}^\circ\|^2/(p-p^\circ)}{\|{Y} - \widehat{Y}\|^2/(n-p)} \sim F_{p-p^\circ, n-p}$$` where `\(F_{p-p^\circ, n-p}\)` stands for the Fisher distribution with `\(p-p^\circ\)` and `\(n-p\)` degrees of freedom. Function `anova` does this. --- exclude: true ```r anova(lm_df[['true']], lm_df[['full']]) %>% broom::tidy() %>% dplyr::mutate_if(is.numeric, round, 2) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 2 × 6 ## res.df rss df sumsq statistic p.value ## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 986 958. NA NA NA NA ## 2 900 885. 86 72.1 0.85 0.82 ``` On the second row, column `statistic` contains the Fisher statistic. The `p.value` tells us the probability that a random variable distributed according to Fisher distribution with `\(87\)` and `\(900\)` degrees of freedom ($F_{87,900}$) exceeds the statistic's value `\(0.89\)`. The fact that `p.value` (`pf(.89, 87, 900, lower.tail = FALSE)`) is `\(0.75\)` does not prompt us to reject the null hypothesis. --- ### Handling `\(p\)`-values The rule of thumb when using the `p.value` reported by a test function is the following: > If, _under the null hypothesis_, you accept to be wrong with probability `\(\alpha\)`, > then > you should reject when the `p.value` is less than `\(\alpha\)` In words: if you are looking for a _level_ (probability of an error of the first kind) equal to `\(\alpha\)`, you should reject the null hypothesis when the `\(p\)`-value is less than `\(\alpha\)` We can decompose the computations performed by ANOVA --- exclude: true ```r setdiff(important_coeffs, # 2 9 22 27 41 49 52 53 59 60 77 88 93 which( (df %>% select(starts_with("x")) %>% purrr::map_dbl(.f = ~ cor(., df$y)) %>% abs() ) > .05) ) ``` ```r lm.0 %>% summary() (svd(t(Z) %*% (Z))$d)^(-1) # Inverse of covariance matrix of coefficients in lm.0 ``` --- ### `step()` --- class: middle, center, inverse ## Algorithms --- class: middle, center, inverse ## Beyond Least Squares --- class: middle, center, inverse ## Ridge regression --- ### Regularized least squares criterion For each `\(\lambda>0\)`, the `\(\ell_2\)` penalized least square costs is defined by `$$\Big\Vert Y - Z \theta \Big\Vert^2 + λ \big\|\theta\big\|^2$$` --- ### Solution to Ridge Regression problem .bg-light-gray.b--dark-gray.ba.bw1.br3.shadow-5.ph4.mt5[ The `\(\ell_2\)` penalized least square cost has a unique optimum: `$$\big(\lambda \operatorname{Id} + Z^TZ\big)^{-1} Z^T Y$$` ] --- ### Proof The penalized least square cost is convex and differentiable with respect to `\(\theta\)` with gradient `$$- 2 Z^T Y + 2 Z^TZ \theta 2 λ \theta$$` The gradient vanishes at `$$(\lambda \text{Id}_p + Z^TZ)^{-1}Z^T Y$$` <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 448 512" style="height:1em;width:0.88em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M400 32H48C21.5 32 0 53.5 0 80v352c0 26.5 21.5 48 48 48h352c26.5 0 48-21.5 48-48V80c0-26.5-21.5-48-48-48z"/></svg> --- ### Pseudo-inverse What happens when `\(λ ↓ 0\)`? -- The limit of `\((\lambda \text{Id}_p + Z^TZ)^{-1}Z^T Y\)` as `\(λ ↓ 0\)` is `\(Z^+ Y\)` where `\(Z^+\)` is the _pseudo-inverse_ of `\(Z\)`: - `\(Z^+\)` has dimensions `\(p \times n\)` - `\(Z \times Z^+ \times Z = Z\)` - `\(Z^+ \times Z \times Z^+ = Z^+\)` - `\(Z^+\)` has minimal Hilbert-Schmidt norm ??? + Constraints 2) and 3) do not always define `\(Z\)` in a unique way + `\(Z^+\)` --- ### Proof <svg aria-hidden="true" role="img" viewBox="0 0 448 512" style="height:1em;width:0.88em;vertical-align:-0.125em;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-size:inherit;fill:currentColor;overflow:visible;position:relative;"><path d="M400 32H48C21.5 32 0 53.5 0 80v352c0 26.5 21.5 48 48 48h352c26.5 0 48-21.5 48-48V80c0-26.5-21.5-48-48-48z"/></svg> --- ### Proposition .bg-light-gray.b--dark-gray.ba.bw1.br3.shadow-5.ph4.mt5[ - `\((Z^T)^+ = (Z^+)^T\)` - If `\(Z^T Z\)` is invertible, `\(Z^+ = (Z^T Z)^{-1} Z^T\)` ] --- class: middle, center, inverse ## Penalized regressions --- ### LASSO Penalty --- ### Orthognal design --- class: middle, center, inverse ## ANOVA --- class: middle, center, inverse ## Iterative methods for OLS --- exclude: true class: middle, center, inverse ## ... --- class: middle, center, inverse ## Ridge regression --- exclude: true ### Solution --- exclude: true class: middle, center.inverse ## Split/Apply/Combine and (Ridge) regression --- exclude: true --- exclude: true class: middle, center, inverse ## Feature engineering --- exclude: true class: middle, center, inverse ## --- exclude: true class: middle, center, inverse ## --- ```r data(iris) require(tidyverse) mutate_y <- function(data) { data %>% mutate(across(where(is.numeric), ~ . -mean(.))) } standardize <- function(df) transmute(df, across(where(is_numeric) , ~ . /sd(.))) select(iris, -Species) %>% standardize() %>% glimpse() ``` ``` ## Warning: Deprecated ## Warning: Deprecated ## Warning: Deprecated ## Warning: Deprecated ``` ``` ## Rows: 150 ## Columns: 4 ## $ Sepal.Length <dbl> 6.158928, 5.917402, 5.675875, 5.555112, 6.038165, 6.52121… ## $ Sepal.Width <dbl> 8.029986, 6.882845, 7.341701, 7.112273, 8.259414, 8.94769… ## $ Petal.Length <dbl> 0.7930671, 0.7930671, 0.7364195, 0.8497148, 0.7930671, 0.… ## $ Petal.Width <dbl> 0.2623854, 0.2623854, 0.2623854, 0.2623854, 0.2623854, 0.… ``` --- class: center, middle, inverse background-image: url(img/pexels-cottonbro-3171837.jpg) background-size: cover ## The End